The UK’s energy sector has made great progress in reducing carbon emissions with the growth in renewable energy. Wind power in particular has been so successful in replacing fossil fuels that grid integration is now becoming the real challenge. As a result of a shortfall in transmission capability, it is estimated that the UK exploits only around 50% of its installed wind power capacity. The consequence of which is that to balance the grid in 2019, the Balancing Services Use of System (BSUoS) payment totalled over £1.4bn, which includes constraint payments to wind farms for discarding power.

Using large volumes of wind-generated electrical power makes balancing the electricity grid difficult. To improve the situation, huge investments in grid infrastructure are required alongside modulating conventional, controllable power plants, demand response initiatives, electricity import and export through transnational inter-connectors and electricity storage, including hydroelectric and batteries. This clearly illustrates the inflexibility of this solution and highlights the need for alternative approaches to storing energy, such as power-to-heat and power-to-gas.

By contrast, in Denmark which has probably the highest percentage of wind power per capita in the world- there is a growing appreciation that successfully replacing fossil fuels with renewables will require far more than wind turbines and batteries, it will require a complete revolution of the country’s economy.

Denmark has been at the forefront of the application of renewable technologies. It turned to renewable energy initially as a reaction to the oil crisis in the early 1970s, when most Danish homes had oil-fired heating. The drivers for change then were cost and security of energy supply. Now, the target to reach net zero by 2050 is driving Denmark to embark on a second renewables revolution.

The expensive ‘hard’ electric approach being pursued by the UK has been eschewed in Denmark in favour of sector (or utility) coupling to provide low carbon heating and cooling to buildings. as the most socio-economic method of, among other things, providing low carbon heating and cooling to buildings. This is based on installing heat networks in urban areas to share energy between sectors, with heat pumps used to supply heat to buildings in remote areas where heat networks are not economically viable.

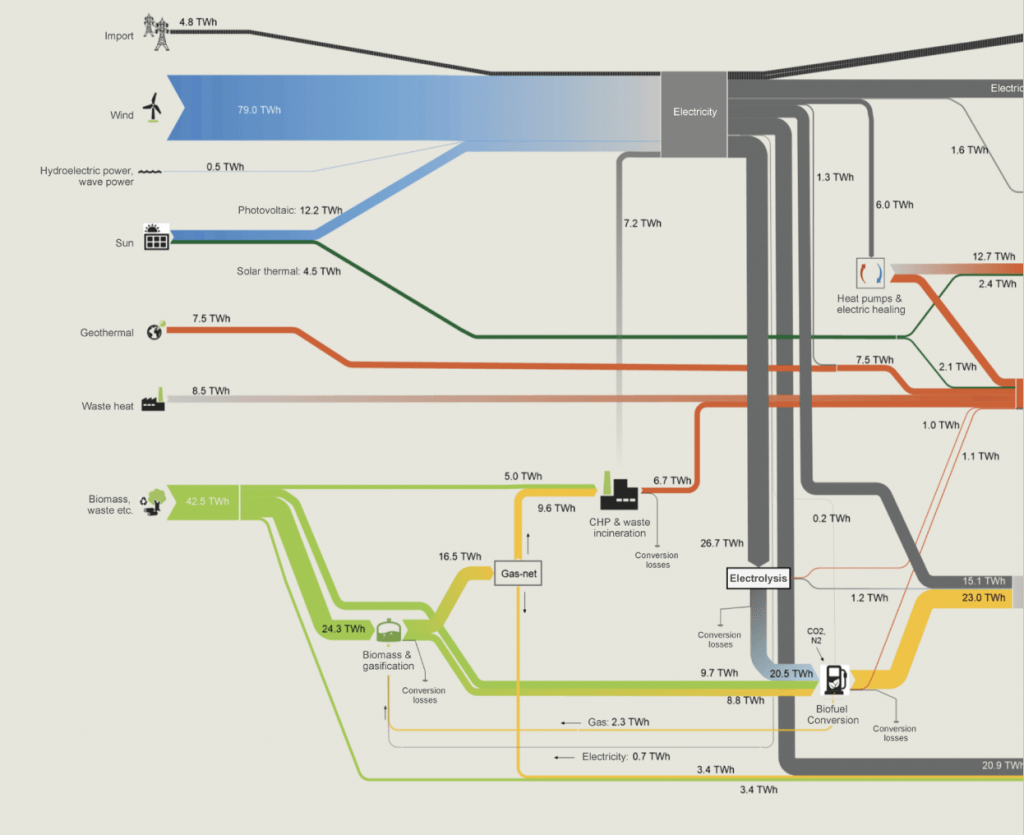

The crucial difference between the two approaches is that hard electrification requires storage using ‘power to power’ technologies (such as batteries), as opposed to storage by power to heat, or power to gas. Power to heat can be activated during periods of abundant wind and/or solar generation with conversion carried out by large scale heat pumps or electric boilers, with the resultant hot water sent to storage for the short term or season-to-season. Surplus renewable power can be used in the electrolysis of water to produce hydrogen gas for applications where there are no ready energy alternatives, such as heavy industry, aviation and transport.

A major benefit of heat networks is that they utilise waste heat from various sources, including power stations, waste incineration and industrial processes (including hydrogen production), to deliver energy cost-effectively. This helps reduce the country’s dependence on non-renewable fuels and improves security of supply.

For Denmark, it is estimated that around 35TWh of heat network heating will be required by 2050, with Heat Pumps supplying an additional 15 TWh (see Figure 1). Some of the heat for district heating will be provided by ‘waste heat’ from the production of electro-fuels, the use of which helps to make the project viable.

To generate sufficient green electricity to both power the country and to produce electro-fuels, Denmark is constructing two ‘energy islands’ in the North Sea, which will be hubs for offshore wind. Initially, one island will supply 2GW of energy, while the other will supply 3GW, but with the potential for both to supply up to 10GW.

According to the UK government, heat networks could contribute 95 TWh, or 20% of the total heat demand, which is almost three times that of Denmark. That would offer huge potential economies-of-scale benefits.

The contrast in both cost and carbon-reduction savings from the UK adopting a sector-coupled approach could be significant when compared with the hard electric approach that the government appears to be pursuing – which is why the UK needs to pause now and consider its options very carefully.