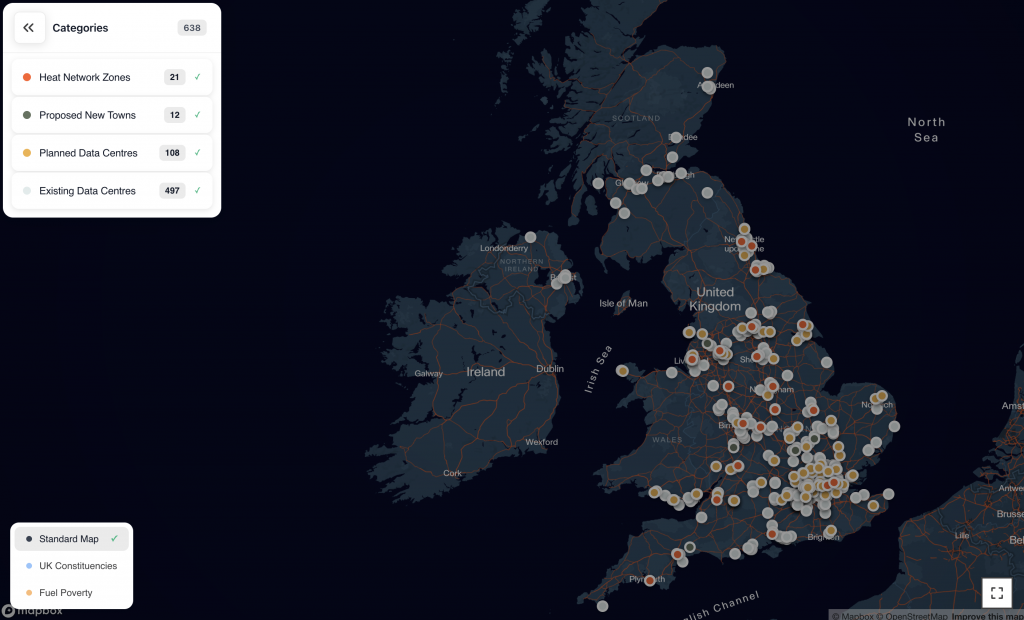

The UK risks missing out on a major source of low-cost home heating if it fails to invest in the Heat Highways needed to capture waste heat from the next generation of data centres. Our analysis shows that these facilities could supply enough heat for at least 3.5 million homes by 2035.

With many existing or proposed data centres situated close to planned new towns, or existing heat poverty hotspots – and in many cases, both – we warn that without action, the UK could end up building a vast new AI infrastructure while leaving the free heat it produces to go to waste, rather than using it to reduce bills and reinforce energy resilience.

“Our national grid will be powering these data centres – it’s madness to invest in the additional power these facilities will need, and waste so much of it as unused heat, driving up costs for taxpayers and bill payers,” said Simon Kerr, Head of Heat Networks at EnergiRaven.

“Microsoft has said it wants its data centres to be ‘good neighbours’. Giving heat back to their communities should be an obvious first step.”

Around Manchester, for example, 15,000 homes are planned in the Victoria North development, and a further 14,000–20,000 in Adlington. Several areas of fuel poverty are clustered around Manchester – but so are over a dozen existing data centres, with four new facilities planned. These facilities could easily supply heat to all of these new homes.

Our research, carried out in partnership with leading Danish energy and sustainability consultancy Viegand Maagøe, examines how this pattern plays out across the UK, and how data centres could provide enough waste heat for between 3.5 and 6.3 million homes, depending on data centre efficiency and design.

Using waste heat to warm homes and other buildings is already common practice in northern Europe, particularly in Nordic countries, where sources of waste heat – including data centres, power plants, incinerators and sewage plants – are required to connect to heat networks. These networks store heat as hot water and supply it directly to homes via heat interface units (HIUs), replacing gas boilers.

In the UK, many cities have already been designated as Heat Network Zones, where heat networks have been identified as the cheapest low-carbon heating solution, with the aim of accelerating their development. From 2026, Ofgem will take over regulation of heat networks, and new technical standards will be introduced through the Heat Network Technical Assurance Scheme (HNTAS), boosting consumer and investor confidence.

However, we do not believe these steps go far enough to fully unlock the potential of waste heat.

“Current policy in the UK is nudging us towards a patchwork of small networks that might connect heat from a single source to a single housing development,” Kerr said. “If we continue down this road, we will end up with cherry-picking and small, private monopolies – rather than national infrastructure that can take advantage of the full scale of waste heat sources around the country.”

“We know that investment in heat networks and thermal infrastructure consistently drives bills down over time and delivers reliable carbon savings, but these projects require long-term finance. Government-backed low-interest loans, pension fund investment, and institutions such as GB Energy all have a role to play, as does proactive leadership from local authorities, who can take vital first steps by working together to map potential networks and commission early feasibility studies.”

Peter Maagøe Petersen, Director and Partner at Viegand Maagøe, added:

“We should see waste heat as a national opportunity. In addition to heating homes, heat highways can reduce strain on the electricity grid and act as a large thermal battery, allowing renewables to keep operating even when usage is low, and reducing reliance on imported fossil fuels. As this data shows, the UK has all the pieces it needs to start taking advantage of waste heat – it just needs to join them together.”

“With denser cities than its Nordic neighbours, and a wealth of waste heat on the horizon, the UK is a fantastic place for heat networks. It needs to start focusing on heat as much as it does electricity – not just for lower bills, but for future jobs and long-term energy security.”

Tables and Data

Upper Bound Scenario:

Full System Model | ||

Installed GW | Calculated Figure (no. of homes) | |

2025 | 2.4 | 1584590 |

2026 | 2.9 | 1914713 |

2027 | 3.5 | 2310860 |

2028 | 4.4 | 2905081 |

2029 | 5.2 | 3433278 |

2030 | 6.3 | 4159548 |

2031 | 7.2 | 4753770 |

2032 | 7.9 | 5215942 |

2033 | 8.6 | 5678114 |

2034 | 9.1 | 6008237 |

2035 | 9.6 | 6338359 |

Lower Bound Scenario:

Full System Model | ||

Installed GW | Calculated Figure (no. of homes) | |

2025 | 2.4 | 877172 |

2026 | 2.9 | 1059917 |

2027 | 3.5 | 1279210 |

2028 | 4.4 | 1608150 |

2029 | 5.2 | 1900540 |

2030 | 6.3 | 2302578 |

2031 | 7.2 | 2631517 |

2032 | 7.9 | 2887359 |

2033 | 8.6 | 3143201 |

2034 | 9.1 | 3325946 |

2035 | 9.6 | 3508690 |

Editor’s note – this assumes avg. annual household heat demand of 11.5 MWh Upper and lower bounds are based on different capture rates, transmission losses and HIU losses. GW figures are based on UK government data : https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/687f74f4fdc190fb6b846868/compute-evidence-annex-final.pdf

Graphics